Zettelkasten - Smart Notes for Smart Learners

Defining "Learning"

"The only way to win is to learn faster than anyone else" — Eric Ries

The term "learning" means different things to different people. Some define the discovery of a new thing as "learning" while others believe that "learning = memorizing".

For the purposes of this article, we will strictly apply the definition of learning outlined by Susan Ambrose et al, 2010: Learning is “a process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of experience and increases the potential for improved performance and future learning.”

It is through this lens that I view all my efforts around learning and coaching.

A System For Smarter Learning

“Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience, both vicarious and direct, on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.” — Charlie Munger

Information is only useful for learning (or even useful at all) if it can be absorbed and turned into knowledge. In my journey of learning to be a better learner, I've come to adapt my own version of the Zettelkasten (German for "slip-box") method of note-taking to build up my latticework of knowledge.

While everyone's needs are unique to them, it is my hope that I can provide you with a starter framework to kick-start your own journey toward smarter learning.

For a much deeper dive, I recommend you read: How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens.

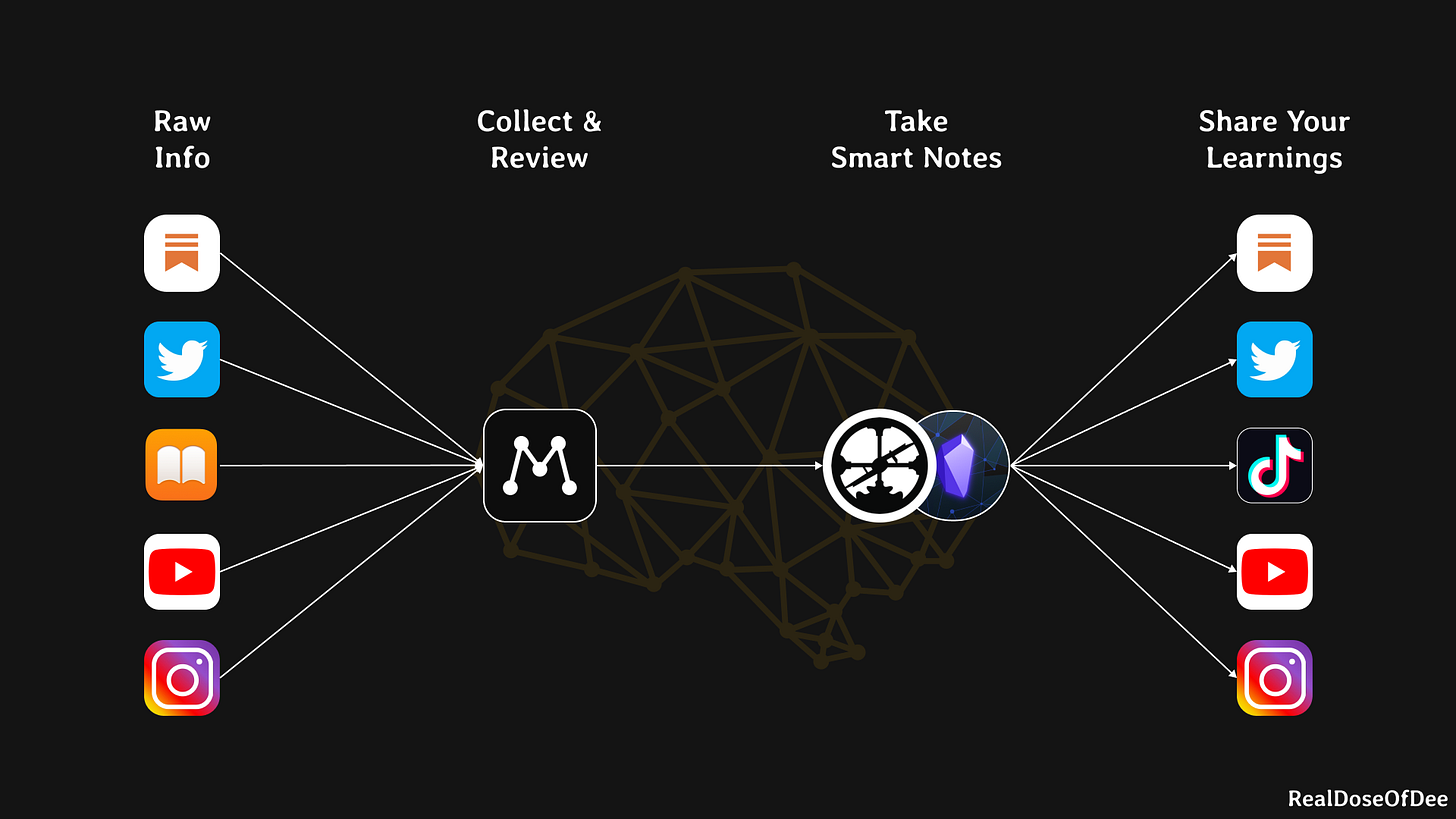

Here's the overview of the sub-processes:

Consuming Information for Understanding

As mentioned above, we're aiming to transform information into knowledge; where we can readily retrieve relevant knowledge when the need arises (ex. writing an article/creating content, applying the knowledge, problem-solving, intentional practice, etc).

To become a more effective learner, one must shift their information consumption habits away from passive to active. This habit applies for all information that you deem interesting/worthy enough to add to your Zettelkasten (i.e. the permanent notes in your note taker).

Different Ways to Consume Information

Here, I will defer to the expert and point you to reading this short Farnam Street article: How to Read a Book: The Ultimate Guide by Mortimer Adler While the article comments specifically about reading, one can apply the same heuristic to all informational content they expose themselves to.

Four Strategies to Apply Here

One: Understand that the relevance of information is not equal.

Use the "Inspectional Reading" method mentioned in the article above: (How to Read a Book: The Ultimate Guide by Mortimer Adler) to assess the content. If you deem the content worthy of adding to your Zettelkasten, please proceed to the next strategies.

Two: Consume information with a "pen in hand", or with your note taker open.

Three: Stay away from copying excerpts verbatim or highlighting text, thinking that you'll revisit it later.

If you find something relevant, take notes instead, expressing your thoughts in your own words. The same goes for non-text mediums: video, audio, and images.

As Sönke Ahrens mentions in his book:

Rereading is especially dangerous because of the Mere Exposure Effect: The moment we become familiar with something, we start believing we also understand it. On top of that, we also tend to like it more (Bornstein 1989).

Verbatim notes can be taken without any thinking involved. (ie. it runs counter to intentional learning). Thus, in the moment, the learner feels like they're going fast, but the net effect which only reveals itself later, when the recollection of that material is required, is that the learner hasn't absorbed the information. From a knowledge standpoint, they're effectively starting from square one.

To use a truism used in the Navy SEALs: "Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast".

Four: Consume with the intention to get the gist. The gist goes into your notes.

The ability to distinguish relevant vs. less relevant information / getting the gist vs. supporting material is a practiced skill. (Ahrens 2017)

Being intentional and actively thinking while you consume information takes effort, it is this concentrated effort that contributes to the neuroplasticity of your learning. In fact, the neurochemicals involved in learning are the same involved with stress. The neuroscience behind how effective learning involves struggle is wonderfully explained by Dr. Andrew Huberman in these two podcast episodes:

How To Focus to Change Your Brain | Huberman Lab Podcast #6 - 36:25

Using Failures, Movement & Balance to Learn Faster | Huberman Lab Podcast #7

Collecting and Reviewing Information

Having a system for collecting and reviewing information (with the mind of filtering the relevant information to add to your smart notes) is the first enabling step to build your Zettelkasten.

In this regard, most learners struggle with self-development either because they're dealing with too much information (information hoarders who have no method for transforming that information into knowledge), or they do not have a habit of exposing themselves to new, relevant information (these individuals tend to "figure it out on their own").

Aside: Information hoarders collect a lot of information (courses, how-to videos, books, etc) with the intention of revisiting it later, but the revisiting rarely happens. In fact, their stockpile of information grows so large that any attempt to revisit the relevant information tends to overwhelm the learner.

This section provides the tools and tactics for how to collect and review information, especially short-form digital information. Later sections will provide you with a way to turn information into relevant and retrievable knowledge.

The Tools

Matter App (freemium) to have all the short-form digital information that you find interesting in one place

Content types include: tweets, YouTube videos, podcast episodes, webpages, Instagram posts & reels

Tags help to categorize content by subject

Use the Queue and Archive for your "Reviewing Information" process (explained below

Readwise (paid, has a 30-day free trial at time of this writing) for extracting eBook verbatim quotes into my Zettelkasten (I'm currently using Roam and testing Obsidian).

As convenient as copy-pasting is, I personally prefer to type book extracts out as a way to trigger my thinking.

How to Collect Information

Do not worry about being judicious during the "Collecting Information" phase.

As long as there is something of interest, save it for reviewing later. This helps prevent getting distracted at that moment by having to consume and review that information; especially useful for the busy individual who needs to stay focused on the task at hand.

Think about this as a "Pre-Fleeting Note". (Fleeting Notes are explained later in the "How to Take Smart Notes" section)

Be judicious about how you tag/categorize what you collect.

If you collect information without tagging or categorizing them, the "Reviewing Information" process becomes more difficult. Without structure or hierarchy, each piece of information loses any context, and all collected information gets diluted to an equal level of relevance (hence, equally irrelevant).

Let your tags/categories get refined as they grow and evolve.

Do not worry about getting your tagging/categorization perfect from the get-go. And definitely do not allow any imperfection to prevent you from getting started.

Revisit your tagging/categorization system from time to time; refine the system to meet your evolving needs.

How to Review Your Collected Information

Reviewing is not passive reading, highlighting passages, or copy-pasting extracts. As mentioned earlier, these methods have all been proven to be ineffective for learning and, in fact, make things worse by giving learners the illusion of "feeling smarter" in the moment.

With this method, we review information with our note taker open (aka pen-in-hand), taking "Fleeting Notes" as we go through the content.

As we review the information, we're performing the following steps in order:

Reducing the stockpile (to minimize overwhelm),

Reviewing the information (extracting relevant information into smart notes), and

Archiving the information (allowing us to revisit if/when a need arises)

Reduce the stockpile: Review your collected information at a regular cadence.

Put dedicated time aside to review what you've collected (clear the pile).

Aim for Collected Information Inbox-Zero with each "review session".

The duration and frequency of each "review session" will be determined by the following factors:

How much content you tend to collect, and at what pace (you can usually tell ahead of time)

How many smart notes you create from the content (difficult to know ahead of time, but you'll build up pattern recognition with practice)

Review the information: Time to be picky.

Your time (and cognitive load) is precious. Be judicious about which pieces of collected information make it into your Zettelkasten.

Archiving the collected information

Once you've reviewed the information, take it out of your queue/inbox and put it in the archive. Some tools (like Matter) will have an archive function, for those that do not, simply create an "Archive" category and move the content there.

Archiving information gives you the option to revisit the material if/when needed in the future while freeing up your cognitive load to focus on what is more relevant to your current needs.

How to Take Smart Notes

This section references various tactics from the book How to Take Smart Notes, specifically around how to write smart notes.

The Tool(s):

Note-taking is incredibly personal, and your tool of choice has to suit your personal needs. My current tool of choice is Roam Research (paid) which has its own technical nuances which I will not explore in this writing. You may wish to consider other tools such as Obsidian (freemium) or any of the ones on Shu Omi's List.

As of this writing, I am trying out Obsidian alongside my Roam usage.

Three Types of Notes

Fleeting Notes

Fleeting notes are quick notes; they are reminders of information.

They can be written in any kind of way (as long as you can recall the context of the note when revisiting it).

They are to be reviewed regularly (I do it daily, or even intraday) and either rewritten as a Permanent Note or archived.

Permanent Notes

Permanent Notes are the ones that make it into your Zettelkasten.

They are never thrown away.

Each Permanent Note contains all necessary information in itself, in a permanently understandable way (if you pick it up 6-12 months from now and read it, it'll still make sense to you).

Permanent Notes are NOT reminders of your thoughts or ideas. Each note contains the actual thought or idea in written form. This is a crucial difference.

They include links/references to other Permanent Notes and tags of related areas of interest. These links help form the connections which make up your latticework of knowledge.

They're always stored in a standardized way, in a standardized place.

Here, I deviate from the classic Zettelkasten system and use a combination of tags and pages (in Roam) and folders (in Obsidian). More on this is in "Tagging Notes for Keywords" below.

Project Notes

Project Notes are notes which are only relevant to one particular project.

They are stored in a project-specific folder.

They can be archived after the project is complete.

Smart Notes for the Forgetful and Busy Ones (like me)

I tend to be incredibly forgetful, and my note-taking needs to compensate for this forgetfulness. Thus, even if I'm writing a Fleeting note, I follow the principle of the "Permanent Note":

Recall: Each Permanent Note contains all necessary information in itself, in a permanently understandable way (if you pick it up 6-12 months from now and read it, it'll still make sense to you).

This way, if I miss a "fleeting note review session" or forget to turn any note into a permanent one, the note still has enough context to trigger my thinking/recall.

The intensity of detail per note is determined by:

The available time I have at that moment, and

The depth/complexity of the information I'm dealing with

As of this writing, this is how I structure every note.

Every note:

Descriptively contains my thought/idea in itself;

I need to be able to revisit this note and not have to question the context or meaning.

This may include my own drawings, charts, or graphics.

Has a bibliography;

Not only the source title but also the specific location (page number, timestamp, etc) to minimize my search time if/when revisiting source material.

If it's an image, I include the URL of the webpage (not the image URL).

Has well-thought-out keyword tags;

This helps me make connections between ideas, thus building up my latticework of mental models.

Includes links to other relevant notes and/or tags to related pages/areas of interest.

This also helps me build my latticework of mental models.

Tagging Notes for Keywords

Pick tags/keywords that contribute to writing and synthesizing thought, rather than for archival purposes.

To once again quote Sönke Ahrens:

The archivist asks: Which keyword is the most fitting? A writer asks: In which circumstances will I want to stumble upon this note, even if I forget about it? It is a crucial difference.

Keywords should always be assigned with an eye towards the topics you are working on or interested in, never by looking at the note in isolation. This is also why this process cannot be automated or delegated to a machine or program – it requires thinking.

An archivist might apply "subject matter" categories such as eCommerce, Marketing, Landing Pages, etc. We see this schema used all the time for blogs to help their readers find relevant articles to consume.

However, your Zettelkasten needs to help you build mental connections (and create "publishable" stuff), not merely read content.

The traditional system of "archival tagging" encourages a list of tags that could quickly grow like weeds, making the tags lose their relevance and meaning. This does not support our need for the timely retrievability of relevant information.

Therefore, on top of topical tags, I tag my notes around ideas, concepts, and first principles that I want to create content about or an area of interest/challenge I'm facing at the time.

Fleeting Notes While On-The-Go

Like most people, my phone is always with me. Whenever I come across any information or thought that I wish to capture, I use the "quick capture" feature on my phone's Roam app to ensure that I do not lose that thought.

Obsidian also has a mobile app. However, syncing between your desktop and mobile app is a paid feature.

Need to get a note down but can't type at the time? Voice-to-text apps like Otter.ai are a great solution!

Aim for Fleeting Note Inbox-Zero

If you do not tend to your garden of "Fleeting Notes", your notes will turn into weeds. Review your "Fleeting Notes" regularly.

Categorizing Smart Notes

Categories, just like tags, are uniquely personal things that evolve as your Zettelkasten evolves. However, I've found that the PARA Method developed by Tiago Forte, is a great starting point for categorizing your Zettelkasten.

PARA stands for Projects, Areas of Interest, Resources, Archived.

As Forte explains it:

A project is “a series of tasks linked to a goal, with a deadline.”

Examples include: Complete app mockup; Develop project plan; Execute business development campaign; Write blog post; Finalize product specifications; Attend conference

An area of responsibility is “a sphere of activity with a standard to be maintained over time.”

Examples include: Health; Finances, Professional Development; Travel; Hobbies; Friends; Apartment; Car; Productivity; Direct reports; Product Development; Writing

A resource is “a topic or theme of ongoing interest.”

Examples include: habit formation; project management; transhumanism; coffee; music; gardening; online marketing; SEO; interior design; architecture; note-taking

Archives include “inactive items from the other three categories.”

Examples include: projects that have been completed or become inactive; areas that you are no longer committed to maintaining; resources that you are no longer interested in

As my Zettelkasten grew, usage patterns started to emerge. To meet my unique needs, I've adapted the PARA method to create my own version. I highly encourage you to start with the PARA method and evolve it as your Zettelkasten grows.

"Adapt what is useful, reject what is useless, and add what is specifically your own." — Bruce Lee.

Revisit and Refine Your Zettelkasten for Deeper Learning

Sticking with the analogy of your Zettelkasten as a garden -- you will take walks in your garden, and you will have to continually tend to it.

Neglecting to tend to your Zettelkasten will fill your garden with the weeds of notes that lose their relevance, thus impeding your ability to retrieve relevant knowledge when required.

Your interlinking Permanent Notes are the pathways in your garden. As you walk around your Zettelkasten garden, revisiting your notes, you may:

See certain things in a new light, which may spring forth new thoughts and ideas, or

Discover that a past string of thoughts/ideas has inconsistencies, gaps in thinking, repetition, or incongruence, and hence needs additional notes to refine your thinking.

Either way, you are deepening your understanding and developing your learning.

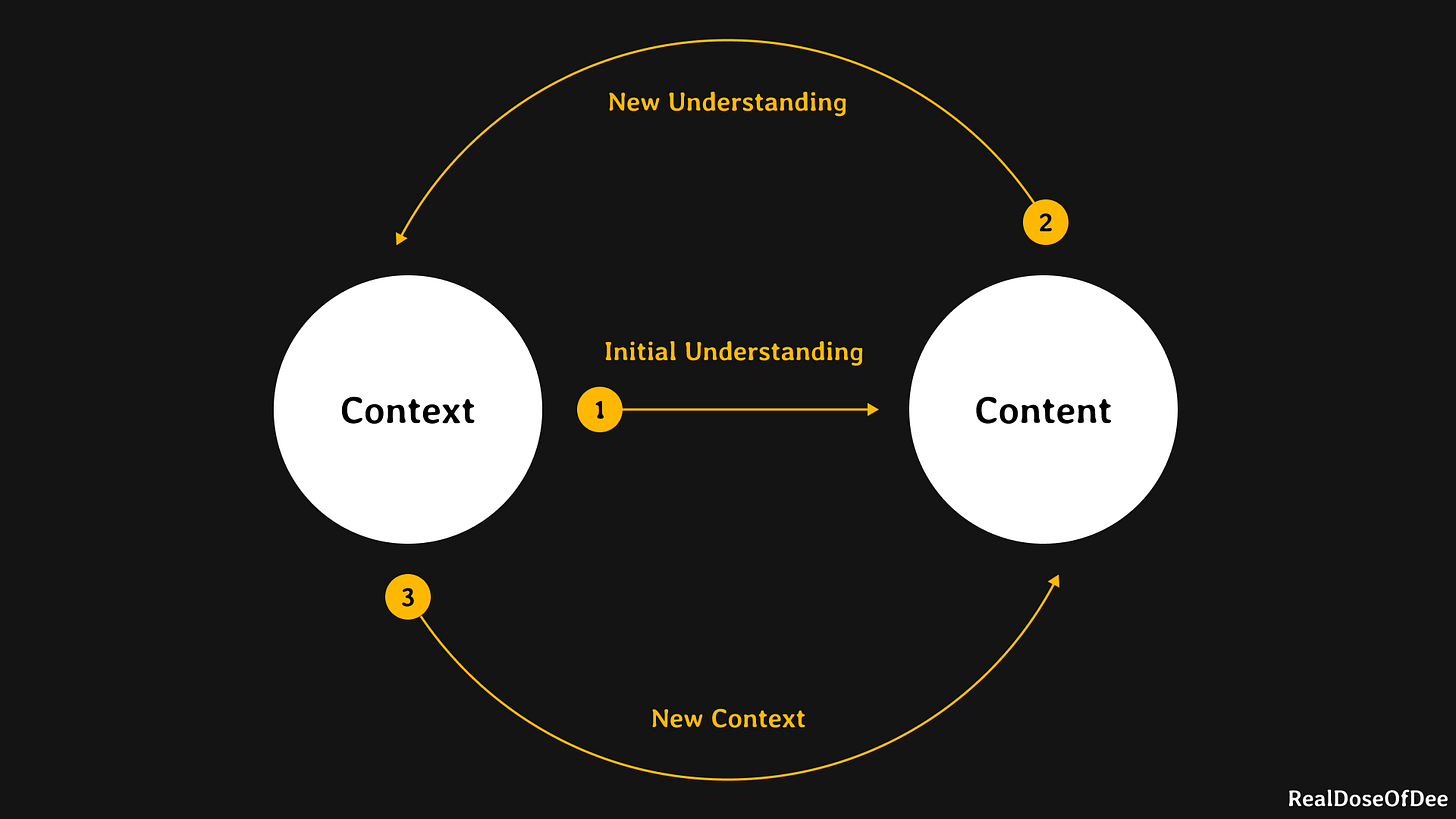

The Hermeneutic Circle to Deepen Understanding

The Hermeneutic Circle refers to the idea that establishing a holistic understanding of information involves a relationship between content (an individual part) and context (a system as a whole).

he Hermeneutic Circle goes like this:

Your current state of understanding (context) informs how you approach any new content, and what you extract from that content;

What you extract from that content alters you and forms your (new) current state of understanding;

Revisiting that same content in this "new current state of understanding" reveals more/different learnings;

And thus the cycle continues.

Hence, the conventional wisdom of "going back to basics". The practiced individual finds new meaning in old information. You deepen your understanding by cycling through the circle; the fancy term being: Iterative Recontextualization.

Revisiting your Zettelkasten is a practical way of applying the "Beginner Mind" aspect of the growth mindset; a great framework for building towards mastery.

Not Just "For the Sake of It"

Naturally, we are most likely to revisit our notes when there is an actual need to do so. This is why the step of "writing and publishing from notes" is part of this Zettelkasten Method; it provides us with a tangible, short-term "actual need" for smart note-taking.

Instead of reviewing information or painstakingly taking "permanent notes" for the sake of it, we now have a short-term outcome of writing and publishing to share our knowledge (and the feedback loop of how our published work is received).

Before you retort, "But I don't have a blog, nor do I want to start one!", I have two counterpoints:

Your writing doesn't have to be long-form. It can take the form of a tweet (or thread), a LinkedIn post, or an Instagram Story / TikTok or YouTube video;

Your content does not have to be published externally. You can write to share knowledge amongst your colleagues or peers, and publish it to your internal company wiki or to a private Google Doc.

The point isn't to turn yourself into an author/influencer, the point is to use your notes to create content, share your knowledge and invite feedback to further your learning.

“By learning, retaining, and building on the retained basics, we are creating a rich web of associated information. The more we know, the more information (hooks) we have to connect new information to, the easier we can form long-term memories... Learning becomes fun. We have entered a virtuous circle of learning, and it seems as if our long-term memory capacity and speed are actually growing. On the other hand, if we fail to retain what we have learned, for example, by not using effective strategies, it becomes increasingly difficult to learn information that builds on earlier learning. More and more knowledge gaps become apparent. Since we can’t really connect new information to gaps, learning becomes an uphill battle that exhausts us and takes the fun out of learning. It seems as if we have reached the capacity limit of our brain and memory. Welcome to a vicious circle. Certainly, you would much rather be in a virtuous learning circle, so to remember what you have learned, you need to build effective long-term memory structures.” — Helmut D. Sachs, 2013.

Writing and Publishing From Your Notes

Once you have a critical mass of notes in your Zettelkasten, you won't have to start from a blank page each time you create content. Instead, you'll have a rich library of connected thoughts and ideas to pull from. That's the beauty of Zettelkasten! (This article, for example, was put together using a compilation of my Zettelkasten notes.)

My Content Creation Process

Revisit and review my Zettelkasten to pick a topic to write about (based on a current interest or need);

Start a new "Project" page for my article;

Review my Zettelkasten for notes that contribute to the main topic idea. Compile them into this page;

Organize/rearrange the compiled notes to aid the structure of my article;

Write the first draft (staying in writer mode while resisting editor mode, you'll see why in the next point);

Shift to editor mode: review the draft, removing anything that does not support or develop my topic;

I also create a separate "Graveyard" doc for this article. When I cut something out of the draft, I move it to the graveyard in case I wish to come back to it later;

As a writer, I have a tendency to address too many things in my content. To most productively counteract this, I write freely and without constraint, but I'm ruthless (but nonjudgemental) when in editor mode. Assessing the merits of the content, rather than judging the writer (myself) helps maintain my sanity.

Review the edited draft (revising as needed);

Publish!

Review and respond to feedback (add relevant feedback to my Zettelkasten)

Get Into A Groove

Get yourself into a “writing and publishing” (or content creation) routine. Instead of struggling to find time in your busy schedule, establish a routine to provide the consistency which helps you get into a groove.

Ease yourself into it, and build up intensity as you go. This gives you the best chance of successfully turning the behavior into a habit that sticks.

What's Next?

I hope this article has inspired you to take your first step toward building your latticework of knowledge.

If that's you, then all that's left to do now is to start (and keep going)!

*I am not affiliated with any of the recommendations for certain books, apps, and other resources in this post.

If this article was valuable to you, I ask that you:

Subscribe to my blog for more

Share this post to share the value

Interact with me in the comments: give me feedback, share a thought, ask a question

Thanks, Dee for sharing your process for learning and building a second brain. Will definitely be checking out Matter and seeing how I can incorporate that into my system. Keep up the good work brother.

Hey Dee! I was first exposed to you on the foundr podcast as a wealth of information. Your insights are much appreciated.

Although I missed the opportunity to apply this treasure trove to Tools of the Titans, I can begin to take a zettelkasten approach to Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. - Speaking of books, I’ve been curious about your fave books, especially around psychology. Future blog perhaps.